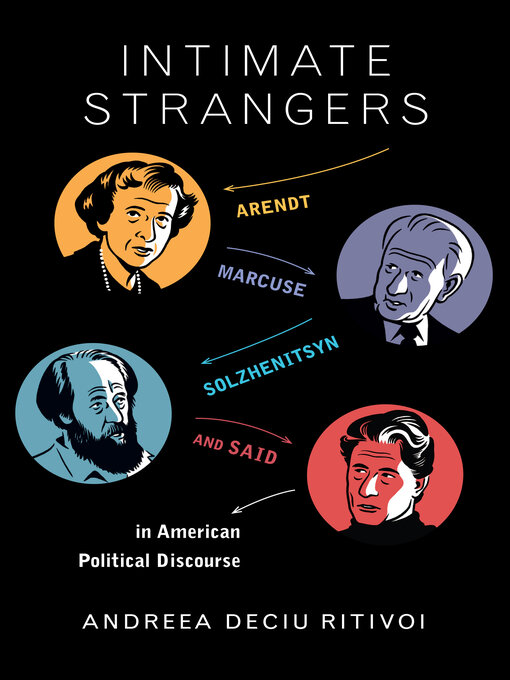

Hannah Arendt, Herbert Marcuse, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, and Edward Said each steered major intellectual and political schools of thought in American political discourse after World War II, yet none of them was American, which proved crucial to their ways of arguing and reasoning both in and out of the American context. In an effort to convince their audiences they were American enough, these thinkers deployed deft rhetorical strategies that made their cosmopolitanism feel acceptable, inspiring radical new approaches to longstanding problems in American politics. Speaking like natives, they also exploited their foreignness to entice listeners to embrace alternative modes of thought.

Intimate Strangers unpacks this "stranger ethos," a blend of detachment and involvement that manifested in the persona of a prophet for Solzhenitsyn, an impartial observer for Arendt, a mentor for Marcuse, and a victim for Said. Yet despite its many successes, the stranger ethos did alienate many audiences, and critics continue to dismiss these thinkers not for their positions but because of their foreign point of view. This book encourages readers to reject this kind of critical xenophobia, throwing support behind a political discourse that accounts for the ideals of citizens and noncitizens alike.

- Available now

- New eBook additions

- New kids additions

- New teen additions

- Most popular

- Try something different

- NYPL WNYC Get Lit Book Club

- Spotlight: Toni Morrison

- See all ebooks collections

- Available now

- New audiobook additions

- New kids additions

- New teen additions

- Most popular

- Try something different

- NYPL WNYC Get Lit Book Club

- Spotlight: Toni Morrison

- See all audiobooks collections